| About the

Author | Preface | Conclusion | A Reassessment

|

The Middle English Bible: A Reassessment

The Bible was translated into English before 1400 and became the most popular medieval book in English. Scholars call it the Wycliffite Bible, attributing it to followers of the heretic John Wyclif, and say that it was condemned and banned in 1407. Henry Ansgar Kelly disagrees, suggesting it was a nonpartisan effort and not the object of any prohibition.

Henry Ansgar

Kelly

Philadelphia: Penn Press,

2016

http://www.upenn.edu/pennpress/book/15577.html

Enter promo code PH41 during checkout to receive a 20% discount.

In the last quarter of the fourteenth century, the entire Bible was translated from Latin into English, first very literally, and then revised into a more fluent, less Latinate style. This outstanding achievement, the Middle English Bible, is known by most modern scholars as the “Wycliffite” or “Lollard” Bible, attributing it to followers of the heretic John Wyclif. Prevailing scholarly opinion also holds that this Bible was condemned and banned by the archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Arundel, at the Council of Oxford in 1407, even though it continued to be copied at a great rate. Indeed, Henry Ansgar Kelly notes, it was the most popular work in English of the Middle Ages and was frequently used to help understand Scripture readings at Sunday Mass.

In The Middle English Bible: A Reassessment, Kelly finds the bases for the Wycliffite origins of the Middle English Bible to be mostly illusory. While there were attempts by the Lollard movement to appropriate or coopt it after the fact, the translation project, which appears to have originated at Oxford University, was wholly orthodox. Further, the 1407 Council did not ban translations but instead mandated that they be approved by a local bishop. It was only in the early sixteenth century that English translations of the Bible would be banned.

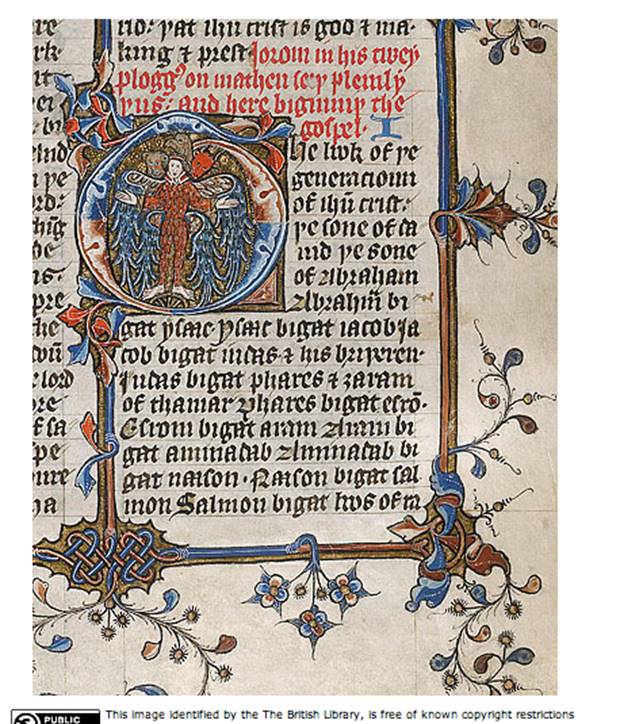

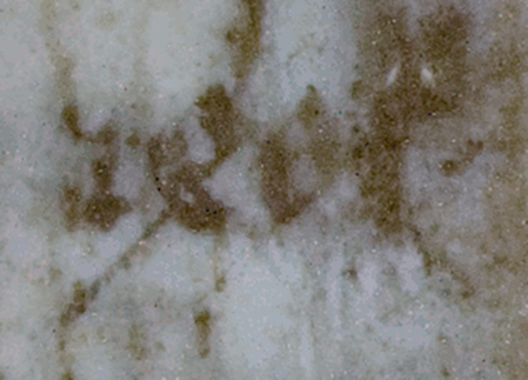

Tetramorph,

Matthew, in English, Wycliffite Bible,

North Midlands, England, 1st quarter of 15th century, 405 x 255 mm.

Arundel

104, Vol. II, f. 251 (detail)

Henry Ansgar Kelly is Distinguished Research Professor of English at the University of California, Los Angeles. He is author of many books, including Satan: A Biography. See satanbiography.com

Table of Contents

Preface ix

Chapter 1: A History of Judgments on the Middle English Bible

¶ The fifteenth to the nineteenth century: from anonymous to Trevisa, Wyclif, Wycliffites 1

¶ Dom Aidan Gasquet’s objections to the Wyclified Bible 6

¶ Recent developments 11

Chapter 2: Five and Twenty Books as “Official” Prologue, or Not

¶ The General Prologue: a latter-day prequel? 14

¶ Simple Creature’s Wycliffite sentiments and his date of writing 17

¶ The conjunction either preferred to or in GP 20

¶ Forsooth shunned in GP and LV New Testament but not in LV Old Testament 22

¶ Simple Creature’s declarations on the Latin prepositions ex and secundum 22

¶ Summary judgment on the General Prologuer (Simple Creature) 35

¶ Other Wycliffite connections disallowed 25

¶ A trial scenario for Simple Creature 27

Chapter 3: The Bible at Oxford

¶ Loss of interest in the Bible in the mid-fourteenth century and its revival by Wyclif (and others) 31

¶ The Oxford theology curriculum and Wyclif’s

participation; Wyclif’s bad Latin 32

¶ Bible study at Oxford:

Graduate students and extracurricular auditors 34

¶ Simple Creature’s unrealistic/inaccurate

ideas about the production of the MEB 39

¶ Why EV before LV? Unsatisfactory first try, or planned preliminary stage, or study help for the clergy? 41

¶ The transformation of EV to LV 44

¶ LV motivations as inferred versus GP motivations as stated 45

¶ Other factors in and out of Oxford, and a suggested down-sizing of the translation and revision enterprises 47

Chapter 4: Oxford Doctors, Arundel (as Archbishop of York), and the Dives Friar on the Advisability of Scripture in English

¶ Thomas Palmer, O.P.: Partially in favor of translation, partially against 50

¶ William Butler, O.F.M.: Completely against 52

¶ Richard Ullerston: Completely in favor 53

¶ Ullerston in English: Against Them That Say That Holy Writ (First Seith Bois), reporting Arundel’s approval of Queen Anne’s English Gospels 58

¶ Dives and Pauper and the Longleat Sunday Gospels 66

Chapter 5: The Provincial Constitutions of 1407

¶ The constitution on Bible translation (Periculosa) and the Middle English Bible 71

¶ Arundel’s 1410 endorsement of Nicholas Love, who recommends the English Bible for the laity 75

¶ Condemnation of Wyclif’s non-biblical propositions on St. Patrick’s

Day, 1411 77

¶ The NEW Wycliffite Bible strategem announced, end of March 1411 78

Chapter 6: Treatment of the English Bible in the Fifteenth Century

¶ The proliferation of MEB copies 82

¶ Misinterpreting Periculosa, now and then 83

¶ Implementing Periculosa: Bishop Repingdon 84

¶ The convocation of 1428 and the role of William Lyndwood 88

¶ The new provincial constitutions of 1431 (all English Scripture to be examined) and Bishop Stafford’s enforcement 94

¶ Lyndwood on Periculosa (1434); excommunication policy (1434) 96

¶ Bishop Stafford’s enforcement of Periculosa (1441) 101

¶ Periculosa and Syon Abbey in the 1440s (?) 102

¶ Bishop Reginald Pecock and the English Bible 103

¶ Archbishop Bourchier’s extreme call-in of English Scripture (1458) 105

¶ Some MEB approvals 106

¶ Other evidences of use, possession, and bequeathal 108

¶ Heresy suspects and English Bibles 109

Chapter 7: End of the Story: Richard Hunne and Thomas More

¶ Thomas More on EV/LV and Periculosa 114

¶ More on Hunne’s trial 115

¶ Hunne’s trial reconstructed 117

¶ More on bishops and the English Bible 124

¶ Good Catholic men step forward: The Douai-Rheims translation 127

Chapter 8: Conclusion 129

Appendixes

A)

A note on the manuscripts, versions, and dates of the MEB 139

B)

Cardinal Gasquet and his critics 141

C)

Present participles

in -inge

and -ende

in EV 147

D) EITHER/OR preferences

in the MEB 150

E) The uses of FORSOOTH 159

F) Simple Creature’s

statement on ex 162

G) The question of a

stylistic break in Baruch

165

H) The translation of secundum by AFTER

or UP 167

I)

Absolute

constructions as discussed in GP and actually treated in EV/ LV 176

J) Other participial constructions in GP and EV/LV 181

K) Summary of participle usage in

Luke 1-6 (Vulgate, EV, and LV) 187

L)

Other constructions discussed in GP 189

M) Some

features not dealt with in GP

192

N) Preface to the Longleat Sunday Gospels 203

O) The Oxford Committee of

Twelve, February-March 1410

206

P) Wyclif’s

Works and the 267 Condemned Propositions, 1411 209

Q) William Lyndwood’s

commentary on the constitution Periculosa 211

R) The Admonition Periculum animarum of

John Stafford, Bishop of Bath and Wells, 1441 218

Notes 223-96

Works Cited 303-27

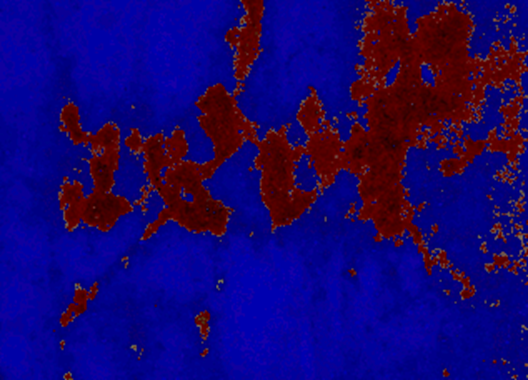

The Date of Richard Ullerston’s

Treatise on Translation

Richard Ullerston (d. 14213) was a doctor of theology at the university of Oxford who wrote a treatise advocating the translation of the Bible from Latin into English. This treatise, Tractatus de translacione Sacre Scripture in vulgare, is preserved in its entirety in the National Library in Vienna, but without name or date. The last leaf of the treatise, giving author and date, is to be found at Cambridge University, Gonville and Caius College MS 803/807 frag. 36. The date has been interpreted as “1401” by Anne Hudson, “The Debate on Bible Translation, Oxford 1401,” English Historical Review 90 (1975) 1-18, p. 10. But since the last digit is obscure and does not resemble the first digit, Henry Ansgar Kelly in Middle English Bible, pp. 53-54, suggests that the date may be “1407.”

Here is a view of the date under ultraviolet light:

|

|

Other views follow, courtesy of Todd Hanneken:

View with first digit imposed on the last:

Here is a high-resolution shot of the whole last page under UV light (129.6 MB):

[600 dpi shot of the G & C Ullerston page]